Earlier this year I went on a workshop/lecture with Professor Lorimer Moseley covering some of his latest pain research. This is a topic I have found fascinating both through my career as a radiographer, through personal injury and more recently as a Pilates instructor and manual therapist. I admit I come to this topic from a unique background as a former radiographer turned Pilates instructor, Neural Reset Therapist, and Rossiter Stretching coach and my journey into the realm of complementary therapies was born from my own experiences with pain, including back issues and migraines. As a result of this and many of my clients wanting to start Pilates as they have heard it helps with pain I have developed an interest in learning as much as I can on the topic to help my clients as well as myself.

The Brain’s Role in Pain

This quote by Howard Schubiner, a leading figure in mind-body medicine is one that many clients find really surprising and rather challenging.

“All pain is real. All pain is created by the brain.”

This quote highlights a crucial point—while pain is a physical sensation, its origin is deeply rooted in our brain’s interpretation of stimuli based on past experiences, emotions, and context.

To clarify, this doesn’t mean pain is “all in your head.” Rather, pain is the brain’s opinion on how much danger we are in, and this opinion can vary widely from person to person. For instance, you might notice that during times of stress, old injuries can flare up, underscoring the connection between our mental state and physical sensations.

The Definition of Pain

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), pain is defined as

“an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with actual or potential tissue damage.”

I feel this definition emphasizes the emotional component of pain and how it can exist even in the absence of visible injury.

This shift in understanding encourages us to consider the complexities of pain. For example, studies show that people can have similar abnormalities in imaging results, yet experience vastly different levels of pain. This suggests that our experiences and perceptions heavily influence how we interpret pain.

In short, the amount of pain you are in is NOT a reflection of how much damage you have.

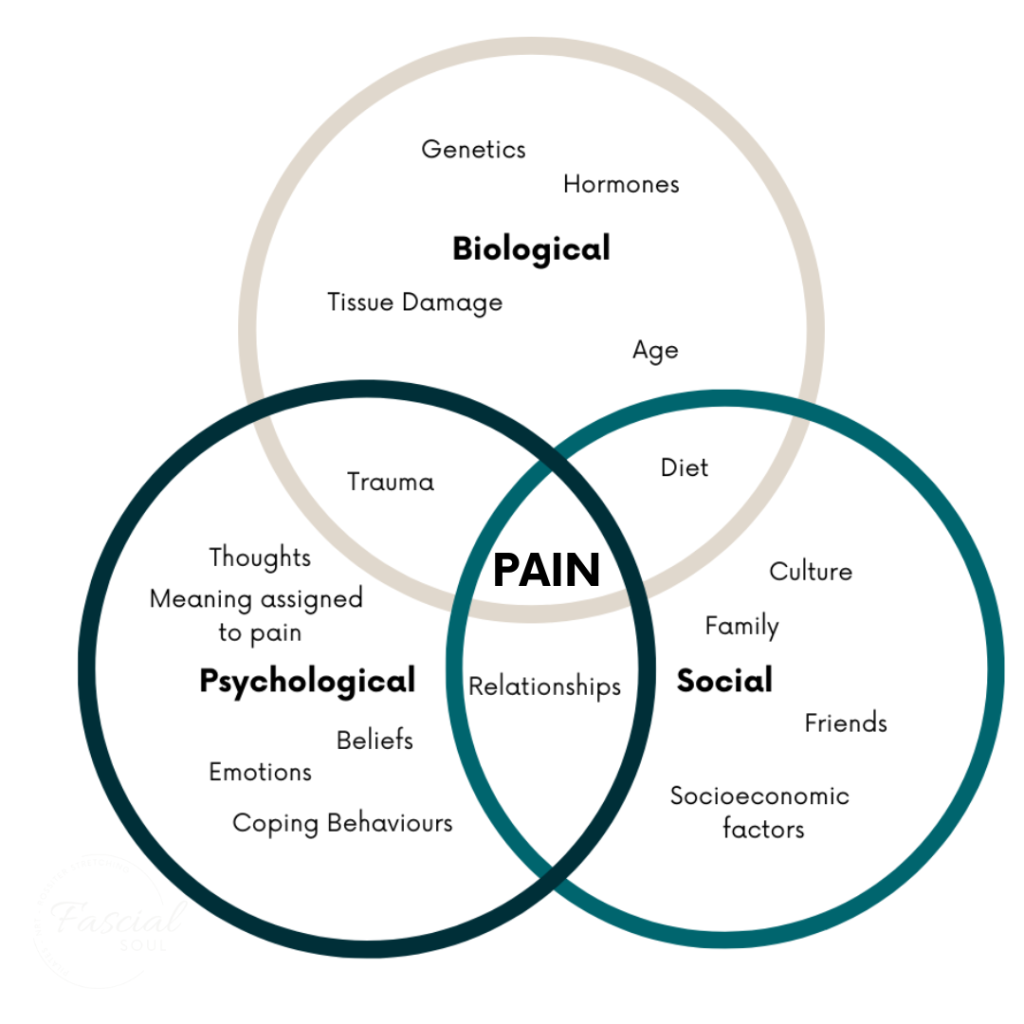

The BioPsychoSocial Model of Pain

As many working with pain clients move away from the traditional biomedical model the need for an alternative model has arisen and in recent years, many practitioners have adopted the BioPsychoSocial model. This means that any time we have pain it is influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors. For example, consider a violinist who injures their finger. The pain they feel may be greater than that of a dancer with a similar injury because the finger is crucial to their profession and identity. The social implications of that injury heighten the perception of danger, leading to increased pain levels. I certainly saw this working in A & E the level of injury and the pain a patient was in were not consistent and talk of high/low ‘pain threshold’ just didn’t seem to explain it.

The Power of the Brain

Our brains want to protect us from danger but also are amazing at learning things whether that is a new language, a musical instrument, or a commonly travelled route through our town (school run autopilot!!). However, this ability to learn combined with the need to protect us means that our brain can learn how to produce pain. Understanding that pain can be learned offers hope. If our brains can create pain responses based on perceived danger, they can also be retrained to reduce these responses. Techniques that promote safety and reassurance can help dial down the protective mechanisms that contribute to chronic pain.

As mentioned earlier the brain produces pain when it perceives danger or feels fear based on information around us and the learnt model we hold in our brain.

In order to retrain the brain we need to update that model, dial down the fear and/or show our brain that we are safe.

There are many ways we can do this and they work differently for everyone, sometimes it will be one thing other times it is a combination:

- Exercise/Movement to update the model held by the brain

- Pain Therapy/Pain Education

- CBT

- Manual Therapies

The work from Professor Moseley highlights the importance of exercise in the use of a ‘sweet zone’ by starting with small movements that the brain knows to be safe and working from there.

However, shifting your perspective on pain has been shown in research to be one of the biggest factors in client recovery

- Recognize You’re Not Broken: Start to shift your mindset. The amount of pain you feel is your brain’s interpretation, not an indication that you’re broken.

- Educate Yourself: Knowledge is empowering. Understanding the mind-body connection can help you navigate your pain more effectively.

- Practice Self-Compassion: Instead of fighting your pain, observe it. This shift in focus can help reduce fear and anxiety associated with pain.

- Explore Positive Sensations: Cultivate awareness of positive experiences—whether it’s feeling the warmth of the sun or enjoying a gentle breeze. These can serve as safe stimuli for your brain.

- Find Supportive Practitioners: Seek out healthcare providers who understand the mind-body connection and can support you in your healing journey.

Conclusion

I hope this exploration of the mind-body connection has shed light on the intricate relationship between pain and our mental states. Remember, you are not defined by your pain. By understanding that hurt does not equal harm, you can begin to foster a healthier relationship with your body and mind.